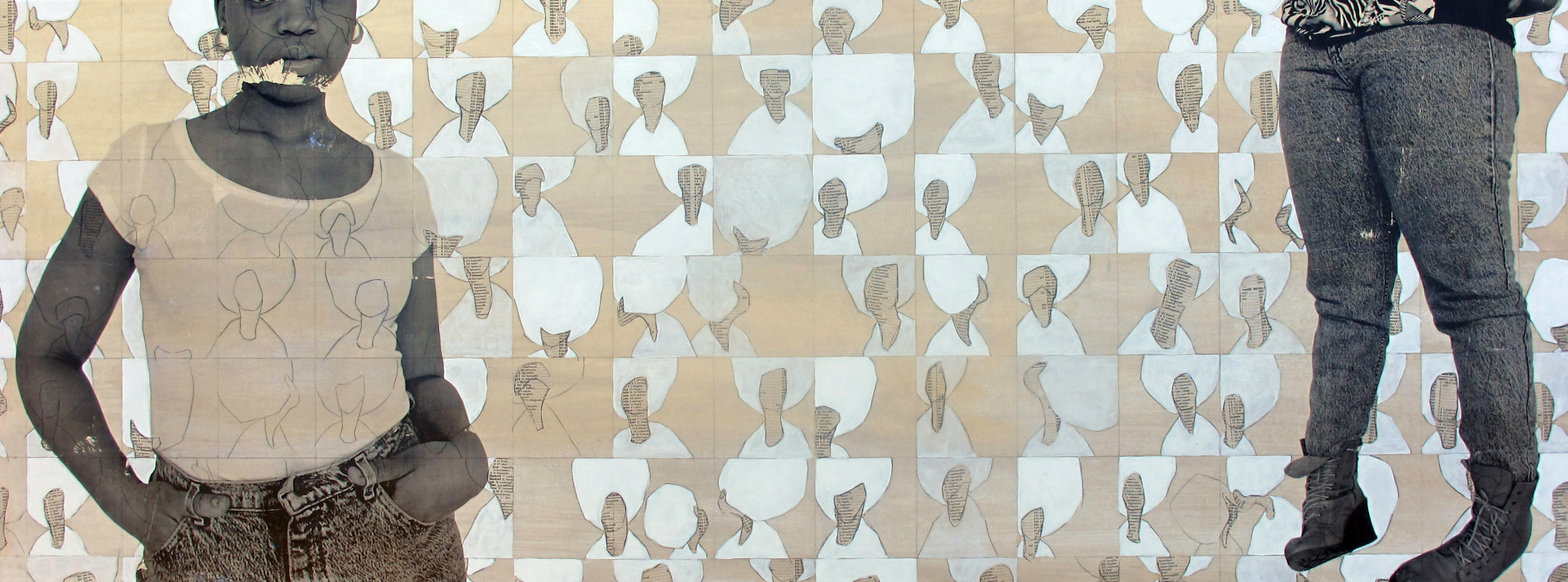

If I asked what you use to lug all your baggage around in, I suppose, like anything, a range of variously sized vessels would compose the list: wallet, fanny pack, tote, knapsack, duffle bag, grocery bag ...

Do you remember the TV show, Baggage? How each contestant revealed their increasingly bigger secrets, one suitcase at a time? What might we find in yours? What revelations wait at the bottom amongst the lint, crumbs, stale Tic Tacs, and receipts? Mind you, not everything we carry with us is heavy and emotional. Like the Advil and ChapStick we keep on hand to soothe us, we accumulate experience, lesson, work of art, song, and story, to be used as needed. Our baggage is something we both actively curate and passively acquire.

In the writing that follows, the poets and authors allow us to peek inside, where we can unpack that which was lost, learned, and found. Sometimes gleaned from the passenger seat of a grandparent’s truck or a therapist’s chair; other times in a flower’s petals, a mango’s skin, or a beetle’s shiny carapace.

No one leaves the house without a little bit of baggage. I know I don’t. Though here certainly isn’t the space to empty mine all over the page. I will admit to one thing you’ll find me carrying around: Grain. I hope this is true for you, too. That you carry Grain with you wherever you go.

- Elena Bentley, Editor

ON REREADING PATRICK LANE’S WINTER IN WINTER NOW THAT I AM AS OLD AS HE WAS THEN | Catherine Owen

In Enoch, Alberta at the River Cree Hotel,

a man’s snores blizzard onto his pillow

and the call to getthefuckouttahere

already came from a drinker down the hall at four a.m.

while all I have to keep me sane is this poem

but it doesn’t sport the white pompom

socks of his Winter 18; it doesn’t own the ease

of his nouns: woman, child, stone, sky,

though why can’t be completely understood.

Overall, it’s a different kind of winter,

decades later, from another body and place,

an itinerant space with a view over the roof,

fields, construction, even in minus thirteen,

building dreams of wealth. It does not have

his romancing of pain, his sonorous repetitions,

that great male cadence. But both poems hold

outsider knowledge of a season, the silent letters

in icicles, the shapes that snowflakes and crows

take on this last day in March.

ORB WEAVERS | Scotty Olsen

The jaundiced orb buzzed above them like a dying pathetic demi-god. It flickered between worlds, spilling an amber stain over the dirty, spring, snow- crusted sidewalk like the enamel of an old smoker’s teeth. Kai tilted his head back into the soft hood of his Diesel sweater and stared into the rotgut belly of the Avenue lamp. A sick kind of glow pulsed from it, casting shadows of thin insect thoraxes, membranes, and veins, turning the night snow aglow somewhere between gold and gangrene.

Kai’s fingers brushed against the folded bills in his pocket again.The edges had lost a bit of their crispness from the constant rubbing. He glanced upward into the lamp’s casing still watching those insects. His grip tightened slowly, pressing the bills, trying to count them without bringing out the wad. Some of that cash he’d made tonight, but most he’d quietly slipped from his own stash. He knew what the truth was; the wad of cash felt like how a rockstar must feel with a sock in their pocket. Kai shifted, suddenly uncomfortable in his own skin, as if those insects up there were crawling all over him. Like when someone mentions the word lice and you can’t help but feel that itch on your head.

Inside the casing, the glass was caked in wings, legs, and pried-open abdomens. Thousands of flies, mosquitoes, and moths fossilized at the bottom. Charred bodies cooking against the plastic like some eternal mosaic. And still more kept coming. Drawn in like it was a reliquary of damn greed, not regret. At the edges, Kai could squint and see some still twitching. Jointed appendages, antennae, and wings tangled together like prayer hands. Just a bunch of beggars. Kai wondered if they were willing to trade anything for one more chance. Or maybe there was something in there with them, slowly tearing open their carapaces and feasting on the soft-poached insides. Did their screams mix with the buzz of electricity?

Idiots. Couldn’t even see what they were diving into. Just one more sucker chasing glow like it meant something.

Kai stared harder.

You think you’re different too, huh?

One clean swoop, pocket some shine, bounce before it burns. Yeah.

Good luck with that.

Kai didn’t move. Just stood there, mesmerized, letting the cool night scrape his lungs. Kai hadn’t heard much from the driver’s seat. Just Ron’s voice, low and clipped. Probably Uncle. Probably about him. What else would they be talking about? Then he heard it.The ’92 red hatchback Civic clicked and settled as the engine cooled. The driver’s door opened. Closed. Then a crunch of footsteps approached him.

LULLABY FOR T.E. | Lee Thomas

in canmore, we bought art for a nursery, imagined

lining up the canvases on the wall, one beneath the other

and now, i put the art in a box in the closet alongside

nursery-dreams and tape it shut.

these mountains were always bear trap teeth: slopes

of wild sunflower and harebell, cliffsides above

meadows, horizon summits still brushed with snow.

in kananaskis, we held hands before the cold plunge

and sat chest-deep in hot springs, let the water draw

lullabies from our pores, a gentle imagining: the weight

of her in my arms, the sound of her small voice,

the art on the walls of her nursery. we share the hush

of her name, your idea. now, i put her name

in the left atrium of my heart and tape it shut.

all the firsts dissipate: showing her the stars

above tunnel mountain. catching minnows

in lake minnewanka. waterfalls and meteor showers,

elk antler sheds and wild strawberries.

without you i sing the memory of her to sleep,

commit her to the mountains,

a cradle of lodgepole pine. trembling aspen.

LISTENING THROUGH THE CEILING | Adam Sol

Whenever Morris played the Romantics on the piano in his apartment, he could hear widow Kropotkin moving around upstairs. Her floors creaked, and even during one of Schubert’s or Chopin’s fortissimos—and there were plenty of them—Morris could hear Mrs. Kropotkin’s heavy tread on the slats above his head. She didn’t seem to respond to Bach or Mozart, and once when Morris had played the opening bars of a Cole Porter tune, he could have sworn he’d heard glass breaking. After that, he left off with the jazz and stuck to the classics.

Morris only knew she was Mrs. Kropotkin because he had looked at the label of her mailbox, and he only knew she was a widow because the “Mr.” was crossed out. Morris wondered if maybe she should replace the marked-up label with a clean new “Mrs. Kropotkin” instead of the smudged “Mr. and Mrs. Leonard Kropotkin,” but who was he to say when maybe her whole life might be wrapped up in being the widow of Leonard Kropotkin?

Morris was a trained concert pianist who’d recently resorted to making a living playing requests at a piano bar called The Dim Bulb. He worried that the drudgery of the work was eroding his technique, and this was why the sounds of Mrs. Kropotkin pacing the floors upstairs started making him nervous. Was she dancing or pacing? Why only the Romantics? Mrs. Kropotkin was quite discerning: when it came to Beethoven, she only responded to the later works, and as for the Moderns, Morris would hear nothing above Shostakovitch orWebern, but as soon as he would touch on a Barber accompaniment or a MacDowell, the floors would set to creaking just as vigorously as if he’d been playing one of Mendelssohn’s Songs Without Words. Over a few emotionally wracked weeks, Morris kept careful notes on Mrs. Kropotkin’s reactions when he played. He experimented with playing some pieces very badly, but it seemed to have no effect. He even transposed a Brahms’s intermezzo from a minor to a major key, but it seemed to Morris that the floor only creaked on those chords which wound up sounding the same—the perfect fifths and minor seconds. It could just have been Morris deluding himself—the pressure of the auditions and his erratic work schedule were certainly taking their toll—but he felt that if he could only figure out the logic behind Mrs. Kropotkin’s creaking, his mind would be at ease. He might even discover that she was a musician herself. Perhaps she could help Morris reconnect with the world that had dismissed him so cruelly.