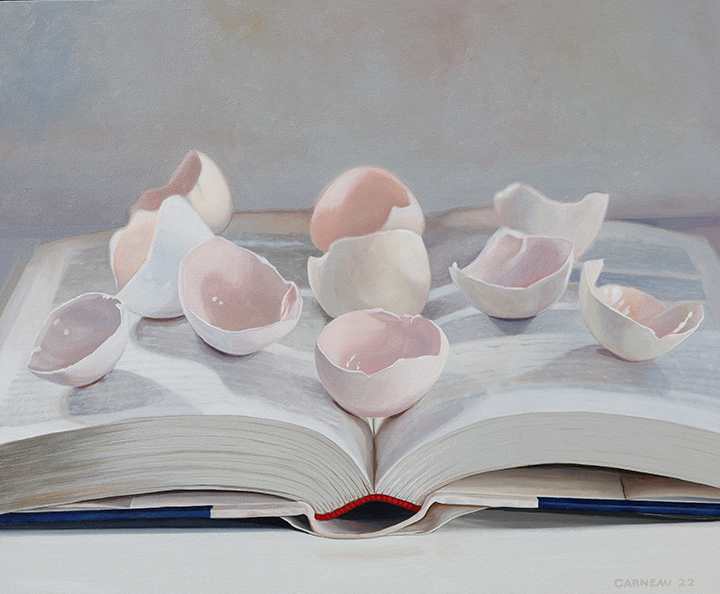

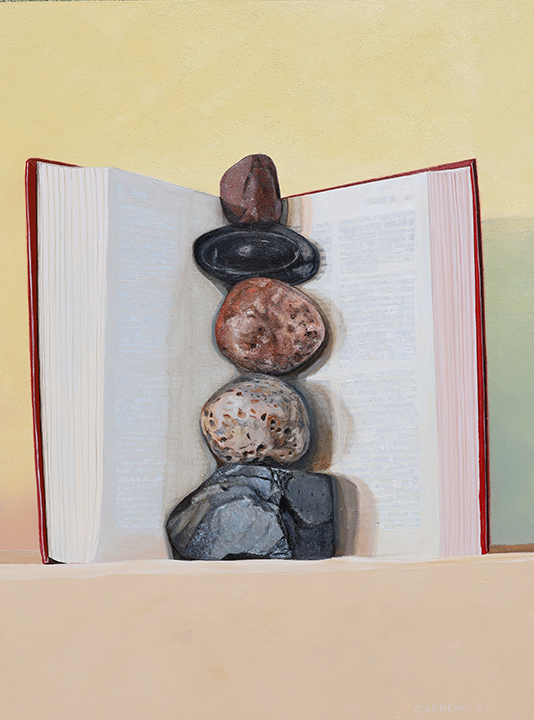

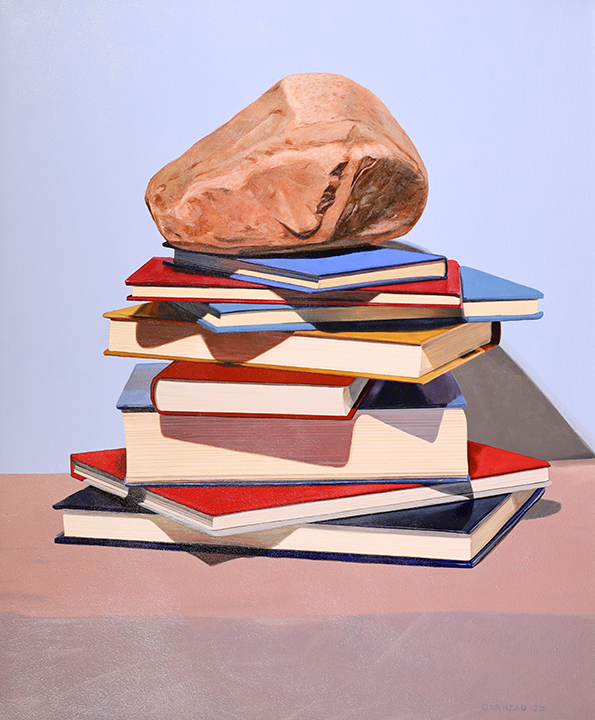

The theme of our fall issue, “Caper and Whorl,” is from John Reibetanz’s poem “Toronto Verandas.” And the first poem, Tom Wayman’s “Neural Music,” is a whorl of images—“in a dream of a broad creek tumbling,” the swirling flow “with its cords and rhythms.” Just in time for Hallowe'en, tricksters abound in these pieces, such as the protagonist who can change into inanimate objects in David Hammond’s delightfully whimsical “Lamping.” Or the shapeshifting baby in Joel Armstrong’s “What to Expect.” David And Garneau's masterful paintings question the nature of visual reality in their photographic realism.

As the poems and prose in this issue adeptly illustrate, writing can help us come to terms with loss and grief--and it can also inspire us to find pleasure and joy. We hope you enjoy these excerpts.

Mari-Lou Rowley, Editor Grain

P.S. At the end of these excerpts, you will find John Geddes's winning story "Home Position," in full as recompense for some overzealous copyediting.

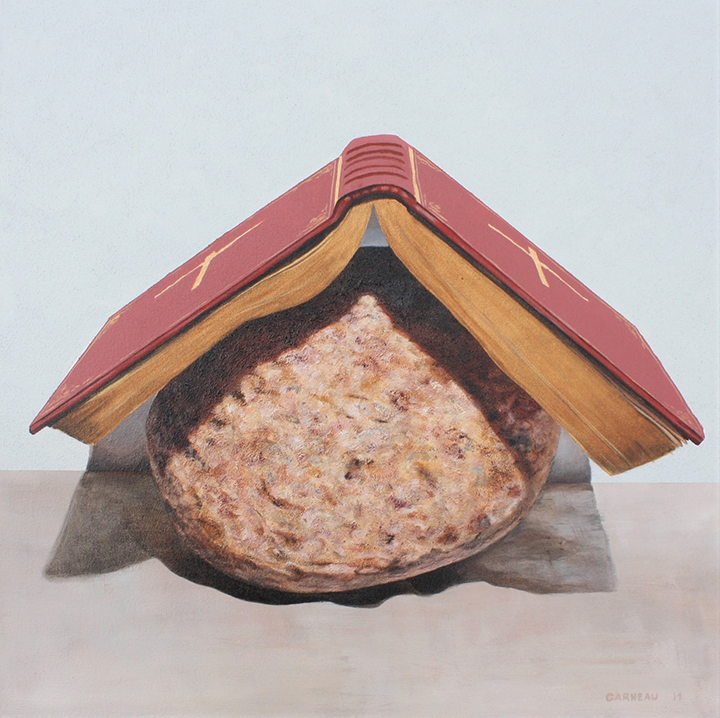

“CAREFUL READER,” acrylic on panel, 76 x 92 cm, 2022.

NO COPY OF THIS IMAGE EXISTS [Excerpt] | Taidgh Lynch

Cast the eye over the River Lagan,

mirrored deep in autumn.

Linger in the shadowy spine

of the half mile

Long Bridge of Belfast.

No need for brush and canvas

to catch what the camera

Cairn II, acrylic on panel, 61 x 50.5 cm, 2022

sees. Fog and steam.

Waterweeds and wood.

A kingfisher dives

for minnows.

* * *

ONE SIDE OF THIS WORLD [Excerpt] | Karin Hedetniemi

In the universe, there are things that are known, and things that are unknown, and in between, there are doors. ~ William Blake

Her suburban bungalow was a time capsule of eighties comfort: plush carpet, swivel recliners, country tchotchkes. Pure air, as if softened by a higher frequency, alchemized into silk. But it was her warm honey voice that smoothed and filled a room. It had the reassuring timber of age, a kind-hearted crepe paper tone. Offering peace as you stepped inside the foyer, chilled from the prairie winter drive, ready for soul work.

If you were a client, the lights would be pre-dimmed, water already boiled for tea. You’d follow her into the kitchen, accept a steaming mug between your cold hands, and take an anticipatory seat at the table.

We had one private session together before she hired me for a side hustle. She needed help marketing her services to a growing client list—someone who could bridge the new technology gap. I was a capable Jill-of-all-trades.

Irene was a clairvoyant medium.

* * *

TORONTO VERANDAHS | John Reibetanz

Settlers retired from army service

shipped the idea with them in sea-chests

along with bungalows from India

where both made sense—the bonneted cottage

shielded from sun by the lace-veiled arcade

though no Canadian wants less sun

or more flat walking-space to shovel

or curlicues under the eaves

where snow can lurk and sink into

the wood unless it’s painted every year

* * *

AZUL [Excerpt] | Dan MacIsaac

Inside the Guatemalan border post, a customs officer glanced over the young man’s passport—identifying him as James Ransom Toller. An officious hand thrust into the traveller’s pack and churned its contents. Toller flinched as quick fingers flickered like wall lizards over his body. Those fingers, fortunately, did not dart to where his money pouch sagged. The young man could not spare a border “fine” or any gifts to the light-fingered. He would need every coin and bill in his pouch to reach his goal of travelling down the long spine of the Americas all the way to Tierra del Fuego.

* * *

CLOUD-GATHERING HANDS [Excerpt] | Olive Scott

Cloud-gatherer,

cultivate the mist within; your soul

blooms with the sound of the

ancient marshes, the purple tundra.

You are the pattern,

but so is everything else;

silk merchant, bison hunter,

Viking ship, silver cypress.

You face the sea-blue sky

and say the poem thrice over;

until you understand:

Let us die in these fields,

this voice is everlasting.

* * *

LAMPING [Excerpt] | David Hammond

After dessert, the guests migrated to the living room. David stationed himself in a wooden chair by a doily-covered end table. His eyes shifted from speaker to speaker, sometimes getting stuck on the bookshelf in between where a small, stoic bust of a woman overlooked the gathering. Marie Curie or Florence Nightingale or Eleanor Roosevelt. Somebody like that. He made a mental note to see an optometrist.

At about the time everyone in the room forgot he was there, David turned into a lamp on the table. This had certain advantages. He no longer had to worry about what to do with his hands, or how to sit without his lower back getting stiff. His ceramic, urn-shaped body rested comfortably on the table, his shade a veil for his thoughts, now free to roam completely unhindered.

* * *

HOME POSITION | John Geddes

There was nothing in your obituary about how at fourteen you could barely write your name. Of course there wasn’t. I found out that late-September morning after Grade 9 typing, when Mrs. Salton told us both to wait after class. We were the only two who had failed a test of rudimentary skills. (First lesson: left-hand fingers on A, S, D, F; right-hand fingers on J, K, L, and the semi-colon key; thumbs hovering.)

You must apply yourselves, she said. Neither of you is stupid.

This was in the mid-seventies. In West Spirit Lake, ‘dyslexia’ wasn’t yet a word. She ordered us to make note of the days when we would be required to show up for remedial drills during lunch hour.

I don’t have to write it, you said, I’ll remember.

For my peace of mind, she said, write it down.

You opened your Hilroy duotang. I averted my eyes to pretend I hadn’t caught a glimpse of your blotched, crabbed, backwards-slanting, ugly scrawl.

I was always going to leave West Spirit and not come back. Except briefly in triumph. So I spared myself the knotted-up dread of the dead-end-town kid who senses a trap. Much later I realized how, from early on, I imagined the black spruce landscape of our childhood as a backdrop. When I got around to V.S. Naipaul, I came to the passage in A Bend in the River where the unnamed protagonist recalls seeing, when he was a boy, a British postage stamp of an Arab dhow. Its beauty made him see the dhows of his daily life differently. That was me. The head frame of the gold mine, monumental. The Beavers and Twin Otters on floats landing on the lake, or taking off again, trailing plumes of spray, picturesque. The old-timers in the grocery store, characters.

Those lunch-hour typing sessions cinched us together. I realized I could help you learn to read and write. Letting you help me with algebra was to even things up. Before long your mother was frying leftover pierogis for me; mine was cutting big squares of carrot cake for you. When we were fifteen, we took driver’s ed classes together, and, the following summer, got our licences in the mail the same day. Soon after, the phone woke me at two in the morning. Your voice like I’d never heard it.

Will your dad let you take his car?

(My father was up by then, standing near me in the kitchen dark.)

I need to take the car, I said.

(A silent second of deliberation.)

I trust you to use good sense.

So I drove you to the edge of town. A police cruiser was parked by the chain link fence that enclosed five half-built houses, a big development by West Spirit standards. Holding his flashlight like a paint brush, one cop aimed at your unblemished face. (Mine was blighted by acne.)

Look at this, said the cop. You’re the little brother, right?

Without waiting for an answer, he spoke too loudly to his partner, who was standing a bit away, panning his own flashlight over the construction site.

That fucker’s little brother is here!

Then they both turned their beams on your brother’s pickup. The cargo bed was stacked with two-by-fours and plywood. When the cops drove up—they must have rolled quietly with their headlights off—he had run for it. Somehow from somewhere he had managed to phone you, and then you phoned me.

That’s a lot of lumber, said the first cop. Greedy, greedy. That’s not probation, that’s jail.

Couldn’t be my brother, you said. He’s home sick in bed.

Bullshit. What the fuck are you doing here anyway?

My brother’s pickup got stolen. Somebody called and said they spotted it out here. I came to see.

You hearing this bullshit? the first cop said to the second cop. Who’s this somebody who tipped you off?

No idea. Anonymous.

Anonymous, my ass. Where’s your brother?

Sick in bed with the flu. Check if you don’t believe me.

Don’t tell me what to do, you little shit.

But they checked anyway, and by then your brother had made it home. Your mother put on a good show of complaining about them waking him up.

My hands on this keyboard: textbook touch-typing form. Never lost it. What else has lasted?

There was the librarian. Way up north for her first job, desperately lonely. She pressed Leonard Cohen’s The Energy of Slaves on me. His name meant nothing. Nobody in West Spirit listened to cool music, just Eagles and Elton John and Doobie Brothers and BTO. During spare, I handed you the book, opened to a short poem. ‘I didn’t kill myself when things went wrong,’ Leonard bragged, ‘I learned to write.’ You read carefully. I didn’t know anybody else who would. I fell in love with the librarian. You were more realistic. In the year before we graduated, you had your first real girlfriend. You told me she wouldn’t do anything but kiss.

It’s not because of her parents. She believes in God.

As you said this, you kept your eyes fixed on my expression to see if I would make a joke. But you hadn’t laughed at that poem.

So I just said, That’s serious competition.

Which was, after all, a kind of joke.

Your brother was ten years older. Once, when you were showering, and I was passing the time as usual with your mother in your kitchen, he came home from work, and said, Fuck me, not again. Your mother said, Ah, ah, ah. Which was about his swearing, not his disapproval of my being there. Another time she told me quietly—again at your kitchen table—that his troubles were her fault.

I was too stupid and too young to know how to be between him and his father, she said. Later, when his brother came, I was not so young and a little bit smarter.

So that was it—hitting. Your brother took the blows, you were shielded. (I could never figure out how to make use of this material: too obvious.) After your mother spoke, I should have asked you about it. Soon we went off to our universities, and then it wasn’t possible. You came to visit me one time, and seemed beaten down. Engineering was a grind, calculus torture. The truth was I didn’t care about anybody but myself in those days. You gave up after a year and went home to take a job at West Spirt Lake Gold Mine Co. Ltd. Later, when I drove up to visit my parents, I hoped not to run into you, and I didn’t.

My mother called to tell me when your brother died. This was when I was finishing my dissertation, two years before my first book. She said he lost control on the switchback turn south of town, always bad in winter. The highway was icy. My father spoke up in the background.

For Christ’s sake, he was drunker than ever, and everybody knows.

Did you hear your father? she asked.

Yes, I said. I heard.

Your mother was sweet to me. Your brother wanted to punch me in the face. Despite all the hours I spent in your home, I never did develop a feel for your father. When you told me your parents were only thirteen or fourteen when they met after the war in a Ukrainian displaced persons’ camp, my first thought about was how differently they spoke English. Your mother’s accent was a dusting on the surface, your father’s kneaded deep into the dough.

That old black-and-white photo you showed me of him with a hawk on his fist left an impression. If I was a painter, I could paint it from memory. We worked out that it was snapped in the early fifties, when the gold mine was new and West Spirt was a last frontier. Your mother told us the story. Some fool shot a mother hawk, and someone else climbed the tree to save the two nestlings. One died, one lived. Some other Ukrainian miner had once overheard your father saying, no doubt when they were drinking, that his father had trained falcons for a rich landlord back in the old country. So they gave your dad the surviving hawk. Many pictures were taken. The sad, beautiful librarian helped us find some clippings in the old West Spirit Prospector files. Your father and his pet hawk were celebrities in a boom town.

The hawk’s death wasn’t written up, though. We had only your mother’s account to go by. One night when your father was underground working the graveyard shift, someone opened the door to the coop he had built and let the hawk fly. It landed on a nearby back porch, where a mongrel lay sleeping on a chain. In a moment, the half-wild dog killed the half-tame hawk.

When your brother died, your old high-school girlfriend called and asked if she could catch a ride should I be driving north for the funeral. By then, she was living in Toronto, working in some sort of government office, not far from my apartment off campus. I didn’t tell her I had spotted her one day on the sidewalk looking perfect.

I don’t think I can get away, I lied. And I really didn’t know him all that well.

We wouldn’t be going for him, obviously, she said.

I don’t know if she made the long drive alone. If she did, I don’t know if her being there would have been any solace to you. I don’t know how your brother’s death hit you. It might have been a relief. Which would have made it much worse. You were protective of him, as much as he would allow. There was the time we tricked him into leaving the bar at the Blue Heron when he was spinning out of control. In the parkinglot, when he dug around in his coat pockets, and realized you had taken his truck keys, and the plan was for me to drive all three of us home, he set out walking instead.

Fuck you, he said when we pulled up beside him as he stumbled along the gravel shoulder of the highway. I don’t ride with your boyfriend.

Nobody bothered to call me when your father died. By then my parents had moved south. My last true connections to West Spirit had gone dry. I saw a Facebook link to the obit and didn’t bother clicking. The two details I cared about were not going to be in there. The hawk. And the way your father would pour himself as much vodka into a kitchen glass as I might pour milk, and then tip in a little Coke. Grey smoke swirling down the centre.

Less than a year after your brother died, I published a short story in a small literary journal about a man who seduces the former girlfriend of his dead brother while he is driving her across the province for the funeral.

I can’t stop reading about birds of prey. In H is for Hawk, Helen Macdonald writes, “The archeology of grief is not ordered.” Ted Hughes has a hawk die in a poem in such a way that its blood mixed with “the mire of the land.” All your father’s hawk would have left behind was a stain on the unpainted scrap lumber somebody had nailed together to make an uncovered porch.

What did we have in common? There was this: every other boy our age in the town of West Spirit Lake hunted in the fall. They’d learn by going out for partridges, come of age by joining their fathers in killing a moose. But ours didn’t hunt, so there were no guns in our houses. I asked my dad once, and he said, Your mother would never cook game anyway. Asking your father wasn’t possible. When would you raise the subject? Not when he was on the couch, watching the hockey game, leaning forward every few minutes to take a careful sip from the glass he had set on the coffee table. He rationed himself: one half-filled tumbler a night. My private theory was that he must have struck a bargain with your mother after those early, angry years.

At least you didn’t go underground every day the way he did. Smart move buying the dealership when the guy who sold Ski-Doos and Evinrudes wanted to retire. How did you swing it? Did your mother have a secret savings account? Or maybe it was your wife—did her parents bankroll you? She was, I estimate, six years younger than us. I’d heard her family name, but wasn’t aware she existed until I learned that you were married. I was sorry to see—Facebook again, pathetically—when she died so young. Still, you had a good twenty years. Breast cancer? Or ovarian? ‘In lieu of flowers, donation to the Cancer Society,’ so I guessed one or the other.

I take it you tried to keep running the business without her. Along with the big-ticket items, you would have stocked fishing rods and tackle, and guns and ammunition. Did you familiarized yourself with rifles and shotguns in order to discuss them with your customers? You would never have taken up hunting, I’m sure of that. But there was the shooting range in the gravel quarry. I have conjured up an image of you there, taking aim.

I searched online to see if anybody demonstrates falconry within driving distance of my condo. I didn’t find anything. But there was a website for a place out in the country where three veterinarians had set up a sort of recovery centre for injured hawks, owls, and even the occasional eagle. They welcome visitors. I drove up last Saturday to have a look. I introduced myself to a young vet who was putting a splint on the wing of a great grey owl. Earlier that morning, a long-haul trucker had brought her a cardboard box containing the impossible bird.

He was in tears, poor guy, she said. Mr. Owl here flew across the highway in front of his semi last night. Not the driver’s fault.

I asked if anybody had ever brought her a hawk that had been attacked by a dog.

That’s one I haven’t seen, she said. The dog would have to be a hell of a jumper!

Guns a problem? I asked.

She pointed out, among the handsome birds recuperating on perches in her long flight cage, a Cooper’s hawk that had, she said, lost an eye, likely to a stray shotgun pellet.

Lucky not to have had his pretty head blown off. I don’t know what we’ll do with him—we can’t return him to the wild with one eye.

Let me care for him, I thought but did not say. Let me take him home.